New research shows that a strong economy alone will not move the

dial on poverty during this parliament raising questions about

the Chancellor's growth first strategy.

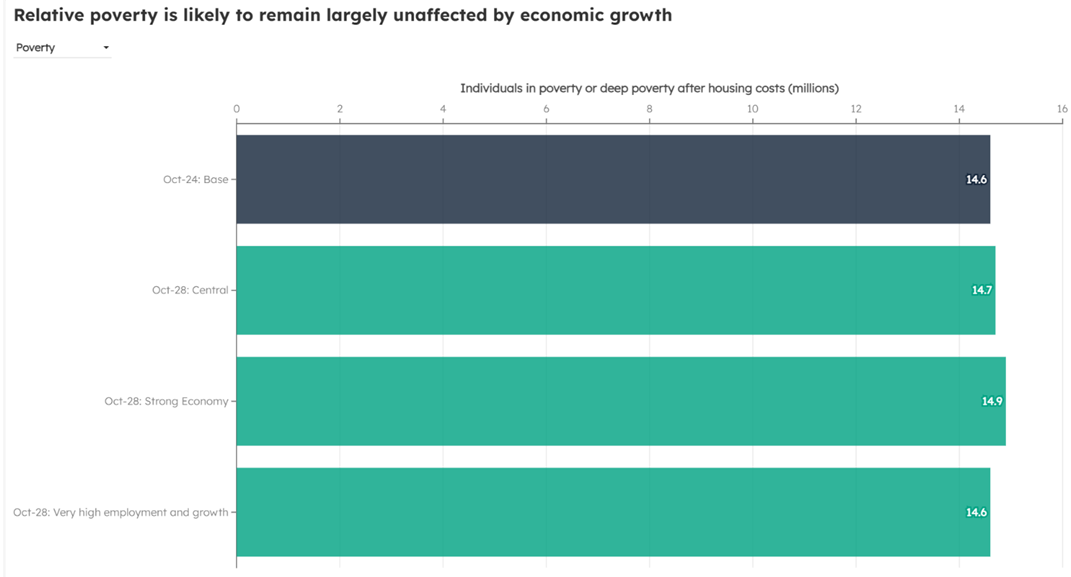

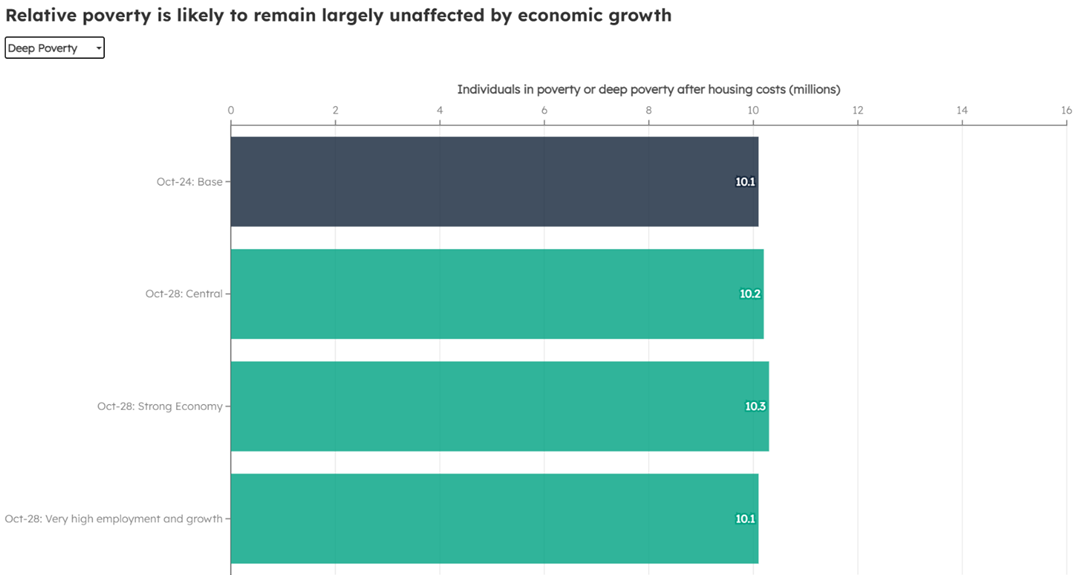

- Analysis based on the OBR's central estimates suggests

poverty will remain broadly flat at around 14 and a half million

people between 2024 and the end of 2028 and this does not improve

even if the UK has the highest GDP per capita growth in the G7

and achieves an 80% employment rate.

- A strong economy can increase wages and jobs but JRF analysis

finds it does very little to reduce working age poverty (broadly

flat at just over 8 million), or child poverty (stays around

4.3-4.5 million) as the gap in living standards between those on

low incomes and middle incomes remains broadly unchanged despite

economic growth.

- JRF is calling on the government to see poverty reduction as

part of its approach to long term and lasting growth. Investing

in social foundations like housing, welfare and public services

must be part of the strategy for securing lasting growth, not

something that can wait to come later.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation analysis shows the risks of the

government's decision to pursue economic growth before improving

the lives of families who have struggled through the last few

difficult years. JRF warns that unless the government invests in

the social foundations now, not only does the economy risk

leaving millions behind, but growth itself may be harder to

achieve and harder to sustain.

The research used estimates mostly sourced from the OBR to look

at what will happen to relative poverty across the parliament

depending on different scenarios for earnings, inflation,

employment and housing costs. If the economy was at its

strongest, with employment at 80% and wages increasing quickly,

there would be a small drop in poverty of around 100,000 to

200,000 by 2028 compared to the OBR's central scenario, but

essentially unchanged compared to 2024.

, Director and Chief

Economist of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation said:

There is something that both millions of families, and rebuilding

the foundations of the economy, have in common: neither can

afford to wait for growth. Families that don't have the means to

stay secure and healthy may contribute less at work, spend less

today and invest less in tomorrow.

“The government's current approach not only risks leaving

millions behind who can least afford it, it also risks failing on

its own terms to deliver sustained and resilient economic growth.

Unless business investment is matched with stronger social

foundations from the start, growth will be harder to achieve now,

and easier to lose to the next economic shock.”

The main scenarios modelled by JRF are:

-

Central – which uses the OBR's central

forecasts for inflation, earnings, employment, and housing

costs

-

Strong economy – which uses higher earnings

and employment forecasts, and central forecasts for inflation

and housing costs

-

Very high employment and growth – which uses

the higher earnings growth forecast, with central forecasts for

inflation and housing costs, and assumes Labour's ambition of

an 80% working-age employment rate is met in 2028. This

scenario is also consistent with UK GDP growth being the

highest amongst the G7 nations over the same period, in line

with the government's primary macroeconomic objective, as is

the strong economy scenario.

We have also looked at a more negative scenario:

-

Weak economy – which uses a forecast with

higher inflation, lower earnings growth, lower employment, and

higher housing costs compared to the central scenario

In the very high employment and growth scenario poverty is made

up of a higher proportion of pensioners and a lower proportion of

working-age individuals compared to the central scenario, given

the fact that employment increases predominantly benefit

working-age adults.